This Dante-themed stroll through the Parco archeologico del Colosseo lets visitors retrace the PArCo’s history through a selection of passages from Dante that recount the history of Rome from its origins to the end of the empire.

The Roman Forum, the Palatine and the Imperial Forums with Trajan’s Column all preserve the tangible, monumental traces of those historical figures to whom Dante gave voice throughout the canticles of the Divine Comedy, together with the pagan divinities worshiped in the central archaeological area’s temples.

The voices of the actors Massimo Ghini, Giuseppe Cederna, Giandomenico Cupaiuolo and Rosa Diletta Rossi will be with visitors all the way, guiding them along the path’s 15 stops.

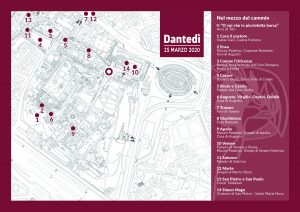

“Nel mezzo del cammin” – The 15 stops of the Dante-themed stroll in the PArCo

“O voi che siete in piccioletta barca, desiderosi d’ascolar…”

Paradise, Canto II, 1-9

The Dante-themed tour of the PArCo begins at its entry point, the Arch of Titus. Massimo Ghini introduces the path and invites visitors to follow him, just as Dante bids his readers not to stray once they’ve arrived at the threshold of Paradise. Minerva, Apollo and the Muses come to the poet’s aid, pointing out the correct path to follow.

Cacus the shepherd

Inferno, Canto XXV, 16-33

There’s an ancient passage on the southwestern flank of the Palatine which Virgil says was taken by Aeneas and the king Evander. Known as the Scalae Caci, its name comes from the mythological giant Cacus, adversary of Hercules. The reason for their clash is represented in one of the frescoes inside the Casina Farnese, a small but precious Renaissance building constructed atop the Palatine, through which Giuseppe Cederna will be our guide: there the giant, who lived in a cave on the Aventine Hill, is depicted struggling with one of Apollo’s sacred oxen, which he has stolen from the hero. For this crime, Dante places him in the 7th Bolgia of the 8th Circle of Hell, where thieves are punished for all eternity.

Aeneas

Inferno, Canto II, 10-36

A piece of a goddess’s face is safeguarded within the Palatine Museum: it’s the Palladium, the statue of the goddess Athena that Aeneas brought with him as he fled Troy for the Italian coast with his father Anchises and son Ascanius. Dante tells us that, through the Trojan hero’s second marriage to Lavinia, Aeneas was also father to Silvius, who went on to found the dynasty that produced Rhea Silvia, mother of the twins Romulus and Remus. Along the banks of the Tiber, this passage, read by Giandomenico Cupaiuolo, brings us to the heart of Rome’s mythical origins, where the Trojan saga is inextricably intertwined with the story of Romulus. This is the bloodline that Augustus wished to eternalize in the statuary cycles that decorate the two exedra of the forum that bears his name.

Cato the Younger

Purgatory, Canto I, 28-93

Dante chooses Cato the Younger, champion of moral integrity, as guardian of Purgatory. Following the footsteps of this incorruptible senator, enemy to Caesar, the voice of Giuseppe Cederna leads us through the political arena of Ancient Rome: the Forum square with the Basilica Aemilia and the Basilica Julia, public spaces used for meetings as well as administrative and justiciary business, and the tribunal of the Rostra, adorned with the rostra (warships’ rams) of the ships captured in battle, from which orators and politicians addressed the crowds.

Caesar

Paradise, Canto VI, 34-72

The Basilica Julia, the Senate House, the Temple of Divus Iulius: the central area of the Forum is marked off by three monuments which to this day tell the story of Caesar’s career and legacy, from his rise to power to his eventual deification at the hands of Augustus. Dante transfers the Dictator’s dynamism and his unstoppable series of victories to the tercets that illustrate, in Justinian’s celebrated speech, the evolution of power through the path of the imperial eagle. Read by Giandomenico Cupaiuolo, the emperor’s speech is an excursus in which one tercet follows another at a frenzied pace, animated by battle scenes and peopled with the main players in the complex affairs of the late Republican Age, an era of which Caesar was both last representative and overthrower, as seen through the same monuments in the Forum that carry on his name.

Brutus and Cassius

Inferno, Canto XXXIV, 55-69

The Temple of Divus Iulius, eternalization in stone of the deification of Caesar made possible by his adopted son Octavian, brings us to the conclusive phase in the revenge plot against the two Caesaricides, which culminated in the Battle of Philippi. The temple’s construction was approved by the Senate in 42 BC, after the defeat of the troops led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Guilty of treason, Dante places them next to Judas, eternally eaten by Lucifer’s three mouths: they are trapped in the fourth section of Cocytus, Judecca, reserved for those who have betrayed their benefactors.

Within each mouth—he used it like a grinder—

with gnashing teeth he tore to bits a sinner,

so that he brought much pain to three at once.

The forward sinner found that biting nothing

when matched against the clawing, for at times

his back was stripped completely of its hide.

“That soul up there who has to suffer most,”

my master said: “Judas Iscariot—

his head inside, he jerks his legs without.

Of those two others, with their heads beneath,

the one who hangs from that black snout is Brutus—

see how he writhes and does not say a word!

That other, who seems so robust, is Cassius.

But night is come again, and it is time

for us to leave; we have seen everything.”

The Temple of the Divus Julius as seen from the Palatine’ slopes

Augustus

Paradise, Canto VI, 73-81

Augustus, born on the Palatine Hill, where he would later build his palace, is the subject of three tercets of Justinian’s speech: he is remembered for his vendetta against the Caesaricides at Philippi, in 42 BC, and for the defeat of Marc Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet at the Battle of Actium, in 31 BC. The poet doesn’t simply list his triumphs: thanks to the emperor’s military feats, the imperial eagle, symbol of power, was able to pacify the then-known world, allowing him to close the doors to the Temple of Janus.

Because of what that standard did, with him

who bore it next, Brutus and Cassius howl

in Hell, and grief seized Modena, Perugia.

Because of it, sad Cleopatra weeps

still; as she fled that standard, from the asp

she drew a sudden and atrocious death.

And, with that very bearer, it then reached

the Red Sea shore: with him, that emblem brought

the world such peace that Janus’ shrine was shut.

Virgil

Inferno, Canto I, 61-75

Having lived in Rome “under the good Augustus at the time of the false and lying gods”, Virgil is the first spirit that Dante encounters on his journey, acting as his “duke” and guide through the circles of Hell and the terraces of Purgatory, up to the Earthly Paradise at the summit of Mount Purgatory. The author of the Aeneid, a major proponent of Augustan propaganda, is depicted next to the Muses in the mosaic from the Bardo Museum, housed in the Imperial Ramp as part of the “Carthago. The immortal myth” exhibition. We can listen to his words thanks to the voice of Giandomenico Cupaiuolo and imagine his presence at court as he climbs the paths up the Palatine to visit the Princeps Augustus in his study.

Horace, Ovid

Inferno, Canto IV, 73-102

The frescoed rooms of the House of Augustus were also host to the circle of the poet Maecenas, promoter and central figure of Augustan poetry. Other members of this circle included Horace and Ovid, two poets that Dante encounters in Limbo together with Homer and Lucan. The four poets are set apart from the other souls in Limbo by their radiance, a distinguishing feature and reminder of the light cast by their art when they were still alive. This meeting during Dante’s passage through Limbo is voiced by the actress Rosa Diletta Rossi.

Trajan

Purgatory, Canto X, 70-93

With a certain amount of surprise, we find Trajan, the optimus Princeps, in the skies of Paradise: although he was a pagan emperor, his particular gifts of humility and humanity have earned him entry into the circle of the Blessed, thanks to the prayers of Pope Gregory the Great. The emperor’s great deeds are immortalized in the Divine Comedy, just as they are in the scenes that twist around the Column that stands between the two Libraries, Latin and Greek, in the Forum that he constructed at the feet of the Esquiline Hill. His story is told by Giuseppe Cederna.

Justinian

Paradise, Canto VI, 1-27

An aerial view shows the monuments in the heart of Rome, from the Capitoline Hill to the Colosseum, covered in snow: these images accompany the words of the Emperor Justinian, who introduces himself to Dante, in the 6th Canto of Paradise, as author of the Corpus iuris civilis, a collection of laws compiled under divine inspiration after Pope Agapetus compelled the emperor to abandon the Monophysite heresy. Justinian, voiced by the actor Massimo Ghini, uses the journey of the eagle, symbol of the empire, to retrace 12 centuries of Roman history: the origins of the Monarchy, the symbols of the Republic and the emblems of power used by Julius Caesar and his imperial successors.

Apollo

Paradise, Canto I, 13-36

For Dante, Apollo is the personification of divine inspiration and as such, the poet invokes him in the preface to Paradise for help in completing his final enterprise. For Augustus, Apollo is the personification of order and morality, and for this reason the princeps identifies himself with the god, including him in his political propaganda and making such use of his cult as to make it a central element in the architectural and decorative schemes of his residence. The comparison between Apollo and Hercules in the Campana Slabs cycle, or the brightly colored fresco of Apollo Citharoedus are some of the images through which Augustus sustains the empire: Apollo is portrayed as a baetylus in the Room of the Masks, in the emperor’s residence, while the portico of his temple on the Palatine was adorned with statues of the Danaïdes, now kept in the Palatine Museum. Rosa Diletta Rossi gives her voice to the supreme poet’s invocation of the god Apollo.

Venus

Paradise, Canto VIII, 1-39

The shafts of light that filter through the columns of the Temple of Venus and Roma accompany a reading of the verses from Paradise in which Dante stops to ponder the true nature of the goddess born of the seafoam off the island of Cyprus. Paying no mind to his mortal nature, the goddess lay with Anchises, king of Troy, to later give birth to Aeneas, father of Ascanius-Julus. This connection would later be the basis for the divine lineage of which Caesar boasted for the gens Iulia, reaffirmed with the dedication of the Temple of Venus Genetrix. Dante, voiced by Rosa Diletta Rossi, lingers over the nature of the love incarnated by the goddess, whose charm lives on in the statues in the Palatine Museum: it’s not a sensual love, as erroneously believed by the ancients, but a pure and disinterested sentiment towards one’s fellow man.

Saturn

In Paradise, the name of Saturn is associated with the 7th Sphere: it is the abode of the contemplative spirits, governed by the angelic intelligence of the Thrones, directly inspired by divine justice. Affairs connected to the administration of justice were conducted in the Temple of Saturn, located along the northern edge of the Roman Forum: consecrated in the early years of the Republic, it was the first location reserved for the publication of public documents and laws, and it also housed the Aerarium, the state treasury.

The temple of Saturno from the slopes of the Capitolium

Mars

In Paradise, the 5th Sphere belongs to Mars: governed by the Virtues, it is where Dante meets the warriors of the Faith. As god of war, Mars is linked to the very genesis of the city of Rome, being the divine father of the city’s mythical founder, Romulus. With the epithet Ultor (‘the Avenger’), the god is commemorated in the temple built by Augustus in the center of the forum: a perennial reminder of the vengeance exacted upon the Caesaricides. Suetonius, in The Twelve Caesars (Aug., 29), writes of a vow taken by Octavian on the eve of the Battle of Philippi: after its construction, the Senate would make all decisions regarding wars and triumphs therein, and all legions traveling to the provinces would depart from the temple and return to the temple to deposit their victorious ensigns.

The Temple of Mars Ultor, in the middle of the Forum of Augustus

Saints Peter and Paul

Paradise, Canto XXIV, 52-75

The northern edge of the Roman Forum, with the southern slopes of the Capitoline Hill, is an area of devotion with strong links to early Christianity. The remains of the Tullianum are found here, the circle-shaped subterranean chamber where the apostles Peter and Paul were held in shackles with other enemies of the Roman people. The condemned were left to die in this prison originally created as a cistern for a spring in its floor (uncovered during archaeological investigations of the area). According to tradition, Peter used the waters of this spring to convert his jailers. The keeper of the keys to Paradise would test Dante’s faith, defined as “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen”—a clear reference to Pauline theology.

Simon Magus

Inferno, Canto XIX, 1-6

The Basilica of Santa Francesca Romana, originally known as Santa Maria Nova, stands on the northern portion of the Temple of Venus and Roma, where the Oratory of Ss. Peter and Paul was established around the 8th century. The site of the oratory, located within a cell once dedicated to the cult of the goddess Roma, was not random: at this site, Peter’s powers were challenged by Simon, a heresiarch dedicated to the magical arts, who began levitating in front of the apostle. When Peter began praying in response, Simon swiftly fell to the ground. The Bible describes Simon’s attempt to pay Peter in exchange for the ability to impart the Holy Spirit, and for this reason he has become emblematic of the practice of selling church offices or sacred objects, otherwise known as simony. Dante places him in the 3rd Bolgia, invoking the sound of the trumpets that signal the Final Judgment.

O Simon Magus! O his sad disciples!

Rapacious ones, who take the things of God,

that ought to be the brides of Righteousness,

and make them fornicate for gold and silver!

The time has come to let the trumpet sound

for you; your place is here in this third pouch.

The Basilica of Santa Fancesca Romana or Santa Maria Nova at the Roman Forum, which embedded the remains of the Oratory of the Sanits Peter and Paul.